The debate surrounding the filibuster is not new. It was a hotbed issue on the campaign trail this year for both Democrats and Republicans. More recently, the Senate voted 52-48 to confirm judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court.

Earlier in her nomination, Judge Barrett's nomination was a controversial issue in the Senate; it even prompted an attempted filibuster by Senate Democrats. As the Senate struggles with partisanship, the fate of the filibuster could not be more critical.

The History of Filibusters in Senate

The United States Senate defines a filibuster as an informal term for any attempt to block or delay Senate action on a bill, or other matter, by debating it at length, offering numerous procedural motions, or any further delaying or obstructive actions.

Although the use of filibusters has risen substantially in recent years, they have a long history within our Senate. In the early days of Congress, both representatives and senators were able to filibuster. As the United States grew, more representatives were added to the House, and revisions limited debate. In 1917, under the Wilson administration, senators adopted Rule 22.

This rule, also known as invoking cloture, allowed the Senate to end a debate with a two-thirds majority vote. In 1975, the Senate reduced the number of votes required for cloture from two-thirds to three-fifths. This meant that 60 of 100 senators would be the new number of votes needed for cloture.

The types of filibusters seen on the Senate floor today were created by a Senate procedure change in the 1960s. At the time, the Senate majority leader, Mike Mansfield (D-MT), developed a new system to handle floor debate. This new system limited the time to debate filibustered legislation while also allowing new Senate business to continue on a separate track. This got rid of the days-long speeches that interrupted the Senate's ability to work.

In 2013, Democrats got rid of the filibuster for executive branch nominees and all judges except Supreme Court judges. In 2017, Republicans got rid of the filibuster for Supreme Court nominees.

Today, filibusters play a large part in the workings of the Senate. The only way to end debate and proceed to a vote is a cloture motion, but 60 votes are hard to achieve. Often, if a filibuster is expected, a bill will not be brought to vote.

Examples of filibusters are easy to come by in the Senate today. Some of the most recent filibusters include bills related to climate change (American Clean Energy and Security Act), gun control (Machin Amendment), and abortion (Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act).

Political Division and the Growing use of the Filibuster

The United States is more politically divided than ever.

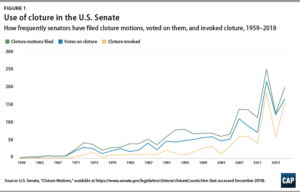

Filibusters play a large role in fueling the political division of our country. The use of cloture in the U.S Senate has skyrocketed in recent years. From 2000 to 2018, an average of 53 cloture votes was held every year, with a continuing upward trend.

Keep in mind that between the years 1917 to 1970, there were fewer than 60 cloture motions altogether. Starting in the 2000s, it became commonplace for minority parties within the Senate to filibuster legislation proposed by opposing parties.

The filibuster works to empower a small number of Senators who may represent a minority of Americans. According to a report from the Center for American Progress, "the most populous state, California--home to nearly 40 million people--has the same number of senators as Wyoming, which has fewer than 600,000 residents.

That means that Wyoming voters have 68 times as much representation in the Senate as Californians." This causes a problem within the Senate because most of the Senate may not represent a majority of Americans.

A filibuster is often used by a minority of senators to prevent a bill that lacks majority support among Americans.

When it comes to passing legislation during periods of a divided government, many bills pass in the House but not in the Senate and vice versa.

Frequently, filibusters are not necessarily the demise of a bill. This could be because it would not have passed in the House or vetoed at the White House. However, during periods when one party controls both the executive and legislative branches of government, filibusters can be fatal to a bill likely to pass in the House.

Here are some examples of filibusters that have occurred in recent Democratic and Republican trifectas.

Bush Administration- Republican Trifecta

S.403- Child Interstate Abortion Notification Act (9/29/2006; vote 57-42)- this bill would have made it a criminal offense to transfer a minor across state lines for an abortion without providing parental notice.

Clinton Administration-Democratic Trifecta

S.3- Campaigning Spending Limit and Election Reform Act (9/27/1994; vote 57-43)- this bill would have created a voluntary partial public-financing system for federal campaigns.

Obama Administration-Democratic Trifecta

S.3772- Paycheck Fairness Act (11/17/2010; vote 58-41)- this bill would have made it easier for women to raise discrimination claims against their employers if paid unequal wages.

Abolishing the Filibuster

Because the word "filibuster" never appears in the Senate rule book, there is no actual rule to abolish. Today, eliminating the filibuster means lowering the 60-vote threshold by amending Senate rules. There are two ways that the filibuster could be repealed. The Senate could lower the 60-vote threshold by holding a vote, or the majority leader could use the nuclear option.

The first way to do this would require the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting. However, abolishing the filibuster is a controversial topic. Therefore, opponents would most likely be willing to mount a filibuster, requiring the supermajority (67 senators) to be in favor. Ironically, the filibuster is what's stopping the filibuster from being abolished.

The more complicated but more likely, way to get rid of the filibuster would be to create a new Senate precedent. This is known as the nuclear option. The nuclear option takes advantage of the fact that a new precedent can be made by a senator raising a point of order or claiming a Senate rule is being violated. In 2013 and 2017, most leaders used this tactic to reduce the number of votes needed to debate nominations.

Some argue that getting rid of the filibuster will not necessarily end the current Senate gridlock. Even without a filibuster, there is still growing partisanship in the United States, and the use of the nuclear option could further destabilize the Senate.

The Future of the Filibuster

Over the past two years, the Senate has set a record of 258 votes to end filibusters. This does not even include the bills that were shelved due to fear of a filibuster.

As partisanship grows in the United States, the filibuster's future could not be more important to young people. Increasing amounts of filibusters have adverse effects on the Senate as well as its legislation.

As America's youngest generation of voters, Generation Z can change the future of American politics. Whatever the future may hold, one thing is for sure: the filibuster has and will continue to affect the United States' legislative landscape substantially.

JSA Voices is a forum in which JSA students can express their concerns about local, state, and federal policies. JSA Voices is proud to provide students from across the political spectrum an outlet for expressing their views on issues that matter to them. The views expressed here are the views of the students and not those of the Junior State of America.